In Antarctica, transport is difficult. Getting around is hard. In the year I will live here, I expect I will be able to count the number of times I leave the base on two hands. Usually we go to places not so far away, as we did with the ice climbing and field course, and we take snowmobiles or snowcats. This is fun, but the ultimate way to get around is to fly. I was expecting a chance to fly, perhaps, towards the end of my stay if I was good and there was a need to maintain some remote field site.

I was then somewhat unexpectedly put on a “copilot training” course. This, I thought while doing the brief session, was n exciting name for some not so exciting field training. It happens that if you fly, you need to be able to use the field kit carried on every aircraft to survive should the plane need to land away from base unexpectedly. But it didn’t seem particularly focussed around planes so I thought nothing more of it until I was called into a meeting and told I was then going to actually be a co-pilot for an upcoming flight.

So, a few days later, I found myself snowmobiling out to our skiway – a slightly flatter bit of snow among the flat snow that serves as our runway – and came to this:

A DHC Twin Otter, the quintessential Antarctic aircraft and the symbol of Antartica’s aviation for the past 40 years. BAS has five aircraft, four of which are these. They are old but reliable and are used by most national Antarctic programs that have air capacity here. They’re an interesting size – bigger than the general aviation Cessnas and Pipers and but smaller than everything else. They don’t have too many bells or whistles (I think someone accidentally broke them off somewhere in their three decades of life).

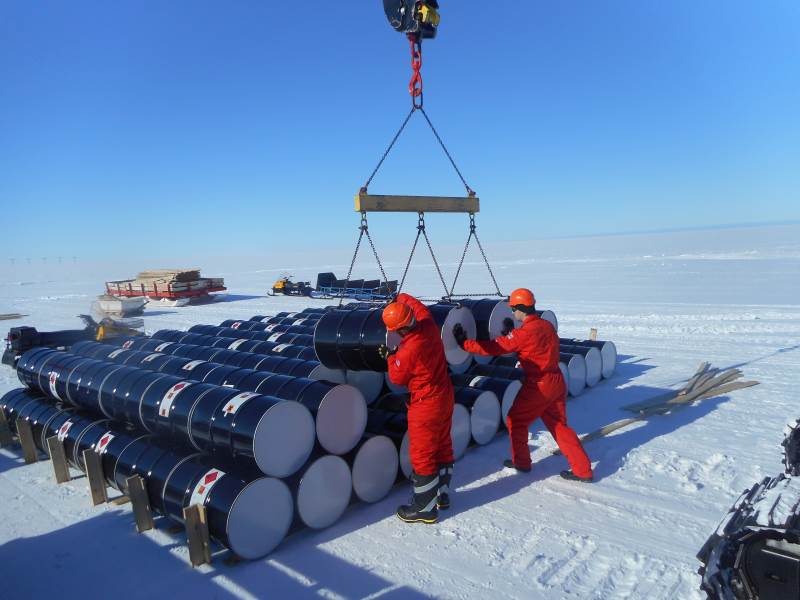

We were flying to take equipment to a field team, “Sledge India”, who were relocating to a new field base at the foot of the Theron mountains. Our flight would take about 90 minutes there, half an hour of unloading, then about the same back – not a long way by Antarctic standards, certainly – more of a milk run. I was very excited. We started by loading the aircraft with our cargo – tents, fuel, sleeping kits, miscellaneous boxes and a snowmobile. A big one too. It’s an impressive sight watching the delicate job trying to get a snowmobile into an aircraft though a door that’s hardly big enough and facing the wrong way:

Off we went. It was a very smooth ride – smoother than I had expected for such a small aircraft. When we had reached the cruising altitude – 3km up – the pilot, Andy, offered the controls to me. This is my third time flying an aircraft and by far the longest – I was flying it perhaps half of the way there. Admittedly, straight and level – but that was tricky enough 🙂 Me, with my “I’m somehow in charge of this machine” look:

The panel of the aircraft was complex but just simple enough that I could understand what was going on. It’s not a massively complicated aircraft, one you could learn and understand quite comprehensively in a way that larger aircraft could never be. It was also pleasantly responsive and you could feel the air on the control surfaces in your hands. My pilot, Andy, patiently answered all my questions and plied me with stories of Antarctic flying!

I was thrilled the whole duration of what I’m sure polar pilots would call a most unthrilling flight. The landscape was starkly white and even – it was impossible to hold a course by looking at something in front because there was, for most of the way, nothing at all for the eye to look at. Ultimately, the horizon served us some black dots that strengthened and spread until this came into good view:

The Theron Mountains. This is a mountain range in the strict sense, but only the very peaks get above the ice and act as a huge dam holding back a vast wall of ice a hundred metres high. Think the Wall from Game of Thrones, just with some mountains for structural support and without trees around it. With nothing living and little eroding it, the rock was stark and clear, with incredibly distinct strata.

We landed to the scene above, directly onto the snow, where the base camp was being established. It was a most beautiful scene these expeditioners had chosen to stay in. It was also very still and quiet – perfectly quiet. That’s an experience, I think, that rarely exists in the world; a place with no noise – not a hum of a machine, distance traffic, vague natural sounds or even slight wind. Can you remember such a time?

We unloaded quicker than I would have liked and set off home. I flew a bit on the way back too. The way back seemed quicker, perhaps because we were flying towards the distant shore. As we approached Halley again, we could see the outline of the Brunt Ice Shelf and all the features that surround it:

The top bit, stretching out to the left, is our ice shelf. Halley is in the middle of that. The coast closer to us is the actual Antarctic coastline, covered in ice as it always is. The cracks in the ice are crevasses caused by the sea ice flowing onto the sea. I will spend, in all likelihood, the next year within the top half of this photo, on that thin-looking veneer of ice. This is my home, resting upon it: