During our time here, we get three main holidays. One is a week off to celebrate midwinter’s in June, the other two, at the very start and the end of our winter, are week-long field trips. In groups of three or four, we head out and spend a few days camping in an area away from base of our choice. We go in staggered weeks to make sure we have enough people to run the base. My week, which was shared with chef Sarah and doctor Nathalie, went to a popular area for such trips known as the Hinge Zone. We were guided by veteran field assistant Ian, who has previously wintered at Halley (the only one of our crew to do so). So, on to the snowmobiles and off we went!

After a couple hours’ trip heading inland towards the continent, the flat uniform ice was broken up by features – large crevasses, cliffs and holes. These were impressive, glistening in the sun, and are created as the ice cap slowly slides off the landmass under us and onto the sea to become the ice shelf. The ice shelf (on which Halley sits) is affected by small tides, and the flex point is around here – hence Hinge Zone. This movement, as well the the sudden change in sub-glacial topography, creates these features and some rolling “hills” of ice. Our kit was hauled with us in 5 towed sledges – 2 of which were entirely spare supplies. We had enough stuff in total to accommodate ten people, and food enough to last us a month.

We arrived at Aladdin’s Cave, the local tourist hotspot (by local standards), and set up camp. The sun had been out, providing excellent contrast and visibility for our drive, but it started to cloud over once we had our tents in place. In previous years, there has been an actual cave at Aladdin’s, but that has long since closed up and now it is a hard-to-describe geometrical feature. I suppose it is best described as a small ice canyon or gorge, with a frozen lake in the middle. Very cool to see. We had a wander around in there before we retired back to the tents for the evening.

The first night was particularly interesting as we had some high winds that night. The tent rattled and flapped aggressively but I slept excellently throughout it all. You tend to sleep well in the field, it seems, as long as you have completely emptied your bladder before you get in your sleeping bag. It is a personal aim of mine not to use our issued pee bottle in my time here..

The next morning we woke to a overcast, snowy scene:

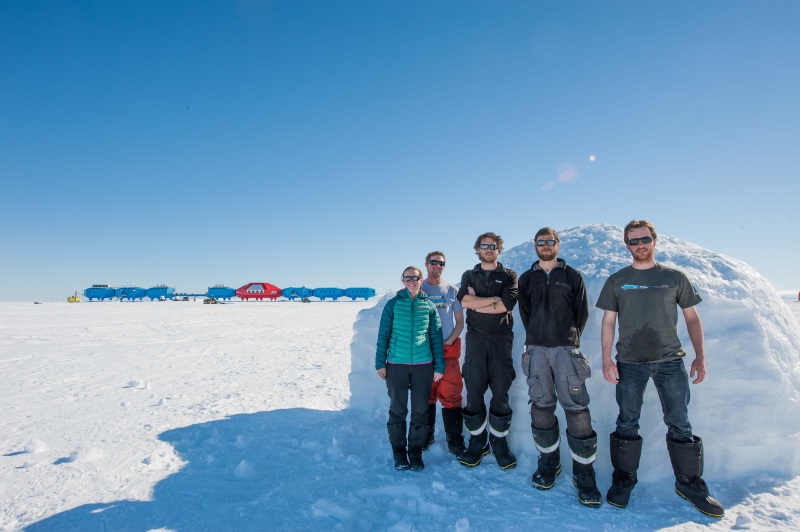

The tent had fared well and the temperature was pretty good – a mere -20°C. Our campsite was located in a chasm – a very old and wide crevasse that now resembles a large valley. And the edges of this chasm were numerous interesting ice features. We set off on snowshoe for one of these features we could see perhaps two kilometers away. The first thing that greeted us was a large bowl-shaped hole in the ice – as vaguely seen behind this pose of my trip-mates:

But the better part was a little bit further. Roped together into Alpine pairs, we trudged into the feature and the landscape changed dramatically. It was a complex, undulating, irregular landscape quite unlike anything anywhere. While easy enough to penetrate and around walk in (thanks, crampons!) is was alien and desolate.

A low, cold sun and a moderate wind that whipped up drifting snow across the strange shapes gave the distinct impression we were somewhere very unusual and special. It felt more like Antarctica than my first day at the base did.

The next day, the visibility was very poor and we struggled to get anywhere new. We instead went to a well-known local landmark, Stoney Berg. This is a large chunk of ice that has become trapped in the ice. Ok, that may not be quite so unusual-sounding, I suppose. What is evidently peculiar is that this ice mound, sticking out of the flat chasm floor, has stones on it. Small boulders sticking out. This, again, may not be unusual to you, but here it’s very strange. We have not seen rock in months! Nothing but ice around here! There’s no obvious way that these rocks could have got here, but current thinking is that this chunk of ice is actually an iceberg that flipped over at some point, scraping the seabed as it did so, and lifted some rocks up with it. Then it got frozen into its current position. Unusual.

However, not being a major geology fanatic ,I satisfied with the observation that they were “probably granite”, we moved on to the highlight of the day: ice climbing! We spent a few hours laying ice anchors, abseiling down an ice cliff and then climbing back up. Good fun. I like ice climbing. Once you get the knack of it it’s quite a bit easier than regular climbing, but you still get a good sense of satisfaction when you make it to the top.

The weather was pretty poor so we went back to camp for our last night of the trip. Our holiday was a little shortened by the crap weather – a problem that plagued all four trips (and indeed, many an Antarctic expedition). Sarah navigated our way back through the whiteness in a suitably advanced and high-tech way:

Despite the weather, I was very happy that we got to stretch our legs off base and explore a place only a few people get the chance to see…