Today is the summer solstice, which means it is midday on the 3-month day we find ourselves in. Because it’s the solstice, and because the favourite date for our arrival to our landing point is the 24th, and because it’s a Sunday, we are celebrating Christmas today! The cooks on board made us a 5-course meal, excellent as always and we got all the trappings of Christmas (including some I didn’t know about!). Also, the crackers on board contain tube balloons designed to be inflated and let go which zoom across the room with a prrrrrrrrrrrrrrtttttttttttt sound – the most entertaining thing to come from a cracker ever. I hope these become standard issue. After, we enjoyed wine, port, Cards Against Humanity, Life of Brian and, my German friends will be happy to hear, Dinner for One.

Yesterday, our very energetic and enthusiastic radio operator officer, Binky, organized carol singing on the forecastle (the bit at the front of the ship). That was also highly Christmasy, with gluhwein and mince pies and snow and looking out over an endless sea of ice. Certainly, we cannot say we haven’t had a white Christmas…

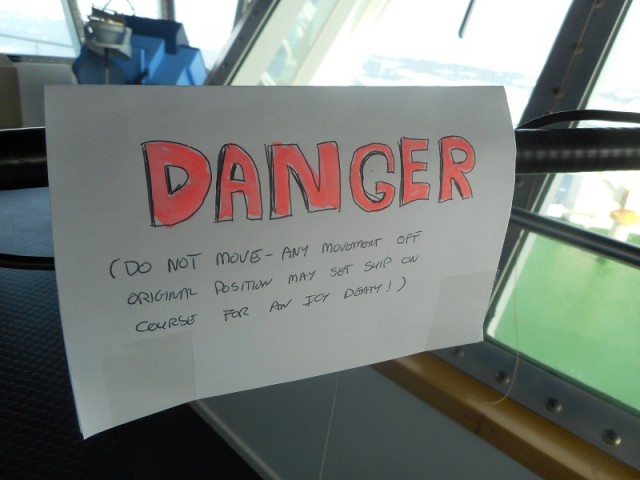

The scene outside today is identical to that scene when we went out to sing. This is because we are beset, which is a fancy nautical term meaning “stuck”, in the ice. We have been now for 36 hours – completely jammed in by closing ice flows. The ice around us on all sides piles up against the hull, in some places up to several metres thick. This sounds alarming, but is actually quite common for ships out here. We are now sitting, waiting for the wind to start blowing Northwards and break up the ice – sea ice flows are like clouds, blown around by the wind and the speed at which it can change can be very fast. The crew have a number of techniques to release us from the tight hold of the ice, my favourite of which is to grab a 30t fuel tank with our crane, stretch it way overboard and swing it back and forth to induce rocking in the hull. We haven’t done this as there’s no where for us to go once free – it’s endless ice to the horizon. A taster of the scenery at Halley, perhaps?

Spirits remain high. For us passengers, there’s not a lot of difference between sailing in a moving ship and sailing in a beset ship – life goes on as usual. Food is served and DVDs are watched. There are some pros and cons of being stuck in the ice, though:

- PRO: The ship has stopped rocking so we now can shower safely without water going everywhere. Similarly, we can use the treadmill without the fear of being thrown off when we hit a chunk of ice.

- CON: The sewage treatment gas exhaust is being sucked into the ventilation air intake, giving a wonderful smell of rotten eggs throughout the cabins.

- PRO: The helmsman can take it easy after a few tough days of ice navigation.

- CON: We’re not making good progress to Halley. In fact, the ice has turned us around and we’re now facing away from where we want to go.

- PRO: The ice is drifting naturally West, which means we’re making 0.2kts (360m/hour) in the right direction. Our engines remain off, so our fuel efficiency is great.

- CON: At 0.2kts, our navigational software is predicting an arrival into the landing site on the 26th of February 2015….

We expect the wind will change and we’ll be out of the ice soon and on our way to Halley, which now is only 300km or so away. A few days ago we passed the German Neumeyer station, although I was asleep at the time (11:00) and so didn’t see it. We have been planning our activities for our arrival, which makes the end of our trip seem more real (even if it is some days off yet at best!). Looks like we’ll be hitting the work hard as soon as we arrive – which no doubt will be a shock after the last few weeks of leisurely cruising…

We stopped to take a ship selfie two days ago. The Captain found a nice iceberg and ploughed the ship into some sea ice next to it. We all assembled on deck and took this photo, in varying levels of festive clothing…

We had more Breathing Apparatus (BA) training. For Commander Tom and me, it was a refresher of the stuff we did at the firefighting training, but for the other three wintering team aboard it was their first time in the kit. Good fun – we’re getting quicker at putting it on! Down from about 10 minutes to a more urgent 3 minutes. The BA is the most important part of our fire response; we haven’t the facilities at Halley to fight a large blaze but we do want to save people who may be stuck in smoke-filled modules. Here, Tom and I pose in our full kit.

Lastly, it has been have noted that our ship’s namesake, Ernest Shackleton, was, with his crew, celebrating mid-summer exactly 100 years ago today about 200km away from our current location. At that time, his ship, the Endurance, was also stuck in ice in the opening stages of a remarkable story of human perseverance against the odds that would end two years and many trials later. I am not expecting we will suffer, as they did, a winter stuck in the ice (at least, not on this ship!), but it does feel like so far we are retracing the footsteps of arguably the greatest Antarctic expedition ever on its centenary.

I wish you all safe journeys (with less delay and difficulty than Ernest Shackleton) to your various families and friends, and a Merry Christmas!